An Iranian band were pursuing the American dream when two of the band’s members’ lives where cut short by someone once considered a friend. But the story of Yellow Dogs should not have ended this way, those who knew the Iranian indie rock band have said.

The shots began to ring out around midnight.

In the early hours of Nov. 11, 2013, as members of the Yellow Dogs wound down in their East Williamsburg apartment, a man made his way across the roofs of neighboring buildings with one goal in mind: kill the musicians who once considered him a friend.

He succeeded in his mission, opening fire on those inside the home and killing two members of the band—brothers—and wounding another before turning his gun on himself.

The story of Yellow Dogs should not have ended this way, those who knew the Iranian indie rock band have said.

The band fled Iran and sought asylum in Brooklyn, New York, to live out their rock and roll dreams. They were on an upward trajectory of critical and fan acclaim, and it was taken from them in a senseless act of violence.

A decade later, friends of the band look back at the tragedy and still search for understanding to make sense of what happened.

The Yellow Dogs Take Shape in Iran in Spite of Oppression and Fear

The Yellow Dogs formed in Tehran, Iran, in 2006 and started playing live in 2007 after solidifying a lineup that consisted of bassist Koroush “Koory” Mirzaei, singer and guitarist Siavash "Obash" Karampour and guitarist Soroush “Looloosh” Farazmand. Looloosh’s brother, drummer Arash Farazmand, also eventually joined the group.

The band, whose name was inspired by the Farsi term for troublemaker, sang in English and was influenced by Western bands like Joy Division, The Clash, Gang of Four and Talking Heads, but also found their own sound in the modern indie rock world.

The band was not inherently political, but they played music that under Iran’s Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance was considered essentially satanic.

“There is a morality police in a way and there's also something called the Gasht-e-Ershad, which basically has to approve all culture that is going to be put out formally to the public. So if you want to release an album, you have to go to the Gasht-e-Ershad. And they will listen and they will literally give you a critique, like the guitars are too loud, or their bass is too loud, or we don't like this singing,” Mark LeVine, a professor of Middle Eastern and African Histories at UC Irvine, who also has written extensively on the music of Middle East, tells Inside Edition Digital.

Though rock and roll is not explicitly illegal in Iran, it is considered “suspect,” he says. As a result, Iran’s rock and roll music scene and others similarly categorized are mostly underground. But playing such music in any setting comes with risks in Iran.

“People would hold concerts in basements and people's homes, the morality police would usually show up because it would get loud. Most of the time you could pay them off. (But) if someone was in the mood to punish a bunch of kids, then they would arrest them and bring them to the police station... If they were in the middle of a broader crackdown, you might actually get people going to jail. And this is the problem with today, you never knew what was going to happen,” LeVine says.

But the Yellow Dogs continued to pursue their passion, which was highlighted in the acclaimed 2009 documentary, “No One Knows About Persian Cats.” The band was featured in the film, which captured the attention of the Western media. And when the Yellow Dogs eventually found themselves forced to choose between giving up performing or seeking political asylum in America so they could pursue their dreams, they chose to move to the U.S.

“If you're a musician in Iran, by definition, if you're not doing traditional Persian music, you're going to face some persecution. You're going to face some level of attempts at repression and censorship, which automatically put you in a category where asylum is at least possible,” LeVine says.

The Yellow Dogs Break Into the U.S. Music Scene

The Yellow Dogs would join fellow Iranian expats Hypernova in New York City. The bands resided in the artist enclave of North Brooklyn.

Both bands had arrived in Brooklyn at the right time. Bands hailing from the borough, including The Hold Steady, The National, Yeah Yeah Yeahs and TV on the Radio, had exploded a few years prior and put a spotlight on the neighborhoods of Williamsburg, Greenpoint and Bushwick. Many believed the Yellow Dogs were in the right place at the right time.

“Any city that goes through a little rush where there's a bunch of bands that are signed that kind of, it's steamrolls and a lot of people always come to New York,” photographer and artist Damon Campagna tells Inside Edition Digital. “It's never an easy place to, I think, make music in New York…(But) it's a place where you can meet a lot of people and there's a lot of cross pollination.”

As they made their music, the members of the Yellow Dogs also worked around the city doing odd jobs to make a living and pay the bills.

Obash, the band’s singer, worked at a bar uptown, where he met Campagna. The pair got to talking about the Yellow Dogs, and Campagna had a funny feeling that he would be a fan.

“They have to be good because everything you would go through to play (in Iran) and then to make it to New York to play here, you have to be pretty solid, tight, professional,” he says. “Otherwise, you wouldn't risk your life to just play, to just be a poor musician. You really have to do it. You really have to be there and in that mindset.”

His intuition was correct.

The Yellow Dogs, he says, were “just f***ing great. They were just a fantastic, check-all-the-boxes, great look, awesome songs, great vocals, technically proficient, and really tight. They had kind of just everything you would look for.”

Campagna was not the only one who felt this way about the Yellow Dogs.

As the Yellow Dogs gigged around New York City, they began to gain a following and in March 2010, just months after arriving in New York City, they performed at the prestigious SXSW music festival in Austin, Texas.

SXSW is “ultra competitive,” Matthew Caws, singer of the acclaimed band Nada Surf, tells Inside Edition Digital.

“It's just super positive… (But) it's competitive artistically, just in terms of numbers,” he says. “You're playing to people who have seen it all, and are seeing it all, and will see it all tomorrow again. If you make your mark there, that's impressive,” he says.

The Yellow Dogs did, indeed, make their mark on the festival. And when they returned to New York City, the buzz around them was greater than ever. Building on their success, the Yellow Dogs and fellow New York-based Iranian rock band Hypernova hit the road together in 2010 and toured the U.S. to rave reviews.

Caws, who met members of the Yellow Dogs at parties thrown by his bandmate Daniel Lorca in his Brooklyn loft, recalls the band “just seemed so happy, and excited. That was probably my biggest takeaway, that they were really twinkly-eyed, really psyched.”

In 2011, the Free Keys, another band out of Iran, arrived in New York City. Their drummer, Arash Farazmand, ultimately began to also play with the Yellow Dogs, Vanity Fair reported. The Yellow Dogs also moved into an apartment with members of the Free Keys. Eventually, problems amongst the men began to arise, according to Vanity Fair.

The Free Keys bassist Ali Akbar “AK” Mohammed Rafie was causing issues among both bands and their friends. In addition to behaving in a way that a female friend of the bands found disturbing, Rafie was behind on his share of the rent, according to Vanity Fair.

Ultimately, Rafie was kicked out of the Free Keys and had to find a way to live on his own, according to reports.

The Yellow Dogs Are Met With Tragedy

As the Yellow Dogs continued to play in New York City, they also dealt with constant harassment from Rafie. He would approach the band in person and contact them on social media and in texts, according to Vanity Fair. Members of the band did their best to avoid him and focus on what they set out to do in America – play gigs and make music.

But their plans came crashing down just after midnight on Nov. 11, 2013. After making his way across neighboring roofs, Rafi arrived at the Yellow Dogs’ apartment and began wreaking havoc. One of his first shots came from outside the home and through a window, striking and killing Ali Eskandarian, a friend of the band who was living in the house. Rafie then entered the home and shot and killed both Arash and Soroush Farazmand.

He also shot a friend of the band, Sasan Sadeghpourosko. He survived. Pooya Hosseini, a member of the Free Keys, was also in the home at the time of the shooting. “That was the worst moment in my life,” he told The New York Times.

Unable to remember the number for emergency services in the U.S., Hosseini tried dialing “110,” the number for the police in Tehran. And when Rafie pointed his gun at him, Hosseini begged for his life. He tried stalling as he made his way closer to Rafie, ultimately wrestling his former bandmate for his gun.

Police eventually arrived on the scene and Rafie made his way to the roof of the house. There, he turned the gun on himself.

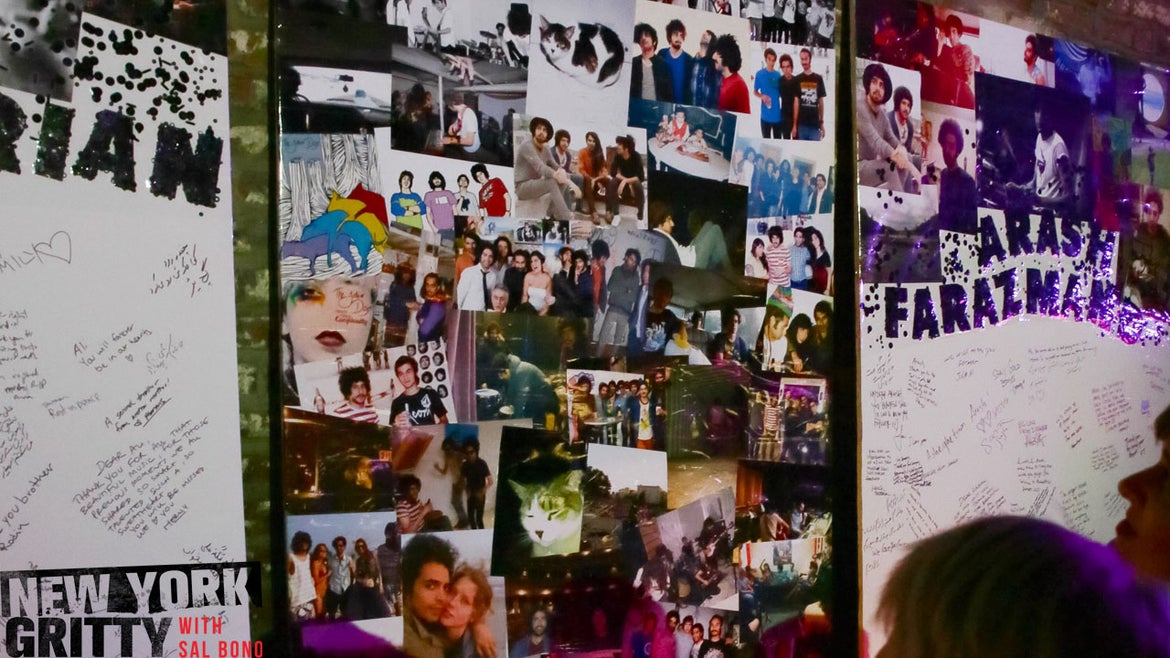

News of the shooting stunned the entire city, but especially rocked those in the music scene who considered the members of the Yellow Dogs their friends.

“My first initial (reaction) was, ‘Jesus, what did they do? Was it political?’” LeVine says. “(But) it was pretty clear, very quickly, that this was not about the (Iranian) government, and it was not about something that had a larger impact. It was just a horrible tragedy about, again, America and guns. It makes that a quintessentially American story. People in the prime of their life doing something they love, gunned down for no reason. That's the tragedy of it.”

Even a decade later, it remains unclear how Rafie obtained a firearm. In the months leading up to the shooting, he reportedly spent much of his time alone. He was heard making extremely paranoid statements, including claims that he was working for the Freemasons, according to The New York Times. Rafie also said he was being prepared for a secret mission to blow up a government building in New York, the New York Times reported.

The day before the shooting, he posted a picture on Facebook of the .308-caliber rifle he would use in the shooting and wrote in Farsi “How’s this?” according to Vanity Fair. “Who to shoot first?” he asked in the comments. Hours later, he carried out his attack.

“It’s just like, why? Of all the bands, of all the things that happen, and it's such a freak incident. This is a freak event. I just, kind of hard to get my head around, how can a group of people who work so hard to make something happen, end in such a terrible way? It just was so heartbreaking. Disappointing,” Campagna says.

Days after the tragedy, a benefit concert featuring Kip Malone of TV on the Radio, Frankie Rose and Nada Surf took place at Brooklyn Bowl, a popular venue located not far from where the Yellow Dogs lived. The show was put on to benefit the surviving members of the band. “Without even thinking for more than a second,” Nada Surf agreed to play the benefit, Caw says.

The atmosphere at Brooklyn Bowl that night was filled with the dualities of lightness and heaviness, as those there both wanted to celebrate and mourn the lives of those lost.

“Light because of the music, and heavy because of the tragedy. It was definitely mixed, but it felt good to be doing something communal,” Caw says.

“Concerts really feel like a place where people are there voluntarily, it's a safe space, and a lucky space, and a soft space. That made that tragedy even more shocking, because a music scene, or a concert, or a practice space is a great place to escape from the world,” Caws says. “It's a refuge, where everything else is beyond those walls of the apartment where the party is, or the club where the show is, or the practice space. You know the real world is there, you know it's out there, but for now, for these next few hours, we are in this safe space. That's one of the best things about it.”

The music of the Yellow Dogs lives on in places like Bandcamp and Spotify. The surviving members of the Yellow Dogs either declined to participate in this story or did not respond to Inside Edition Digital’s requests for comment.

“There's a legacy of art that you leave behind. Visual art, or music, or poetry, or whatever you do. You have something left behind. And the thing we have from Yellow Dogs is, oh yeah, that's like where that guy shot up all those guys, and then there was no more band. And that's not fair,” Campagna says. “It's not fair to the guys who died. It's not fair to the guys who survived. There aren't enough people saying, ‘oh yeah, remember the Yellow Dogs? That band was awesome.’”

Related Stories